Coming Home: Campbell Vietnam vets on returning to campus after war

John DeLamater was 23 when he returned to Campbell after being drafted to the Air Force in 1966. He had seen a lot in his year and a half in Vietnam.

The 18-year-olds he shared a dorm with seemed impossibly young and “didn’t care much about the academic part of school,” DeLamater remembers. He had been like them once, but his priorities had changed after the structure of military life. He moved out of the dorms as quickly as he could, studied hard and graduated in 1973 with a Business Administration degree.

DeLamater is one of 8 million veterans who served during the Vietnam War, representing a unique era of American history in which the hotly contested military involvement and a continuous draft from 1965 to 1973 meant that many men serving abroad were conflicted about their service and sometimes met with lukewarm support from their friends at family at home. The tension was even greater on college campuses, where anti-war sentiments were often more prevalent.

Despite a great percentage of Vietnam veterans using the GI Bill’s education benefits, higher-education institutions — roiled by anti-war protests, shifting priorities and changing demographics — were ill-equipped to handle a surge of returning servicemen seeking an education while grappling with the toll of the war.

While a tense atmosphere may have prevailed at other institutions, DeLamater remembers receiving a warm welcome from his classmates upon returning to Campbell. He originally chose the school for its small class sizes and personal feel, and while his experiences set him apart from younger students, Campbell was still home. DeLamater might have had a typical college experience had he not been drafted in 1966. His father served in the Air Force in World War II, so DeLamater decided to follow in his footsteps and chose Air Force over Army when he enlisted. He arrived in Saigon in January 1969.

“We went over and we did our job. That’s all we could do,” DeLamater puts it simply. In Saigon, his duty was to bring incoming mail off the flight line in Unit 1600 of the Postal and Courier Service (PCS). Vietnamese workers would unload mail from the planes, and DeLamater’s 12-hour shift was spent separating that mail and moving it to trucks to be delivered across the country. The base received more than a million pounds of paper mail every day.

DeLamater left Saigon on Aug. 24, 1970. He had been given the option to extend his time in Vietnam by six months in order to leave the Air Force six months early and return to student life.

___________________

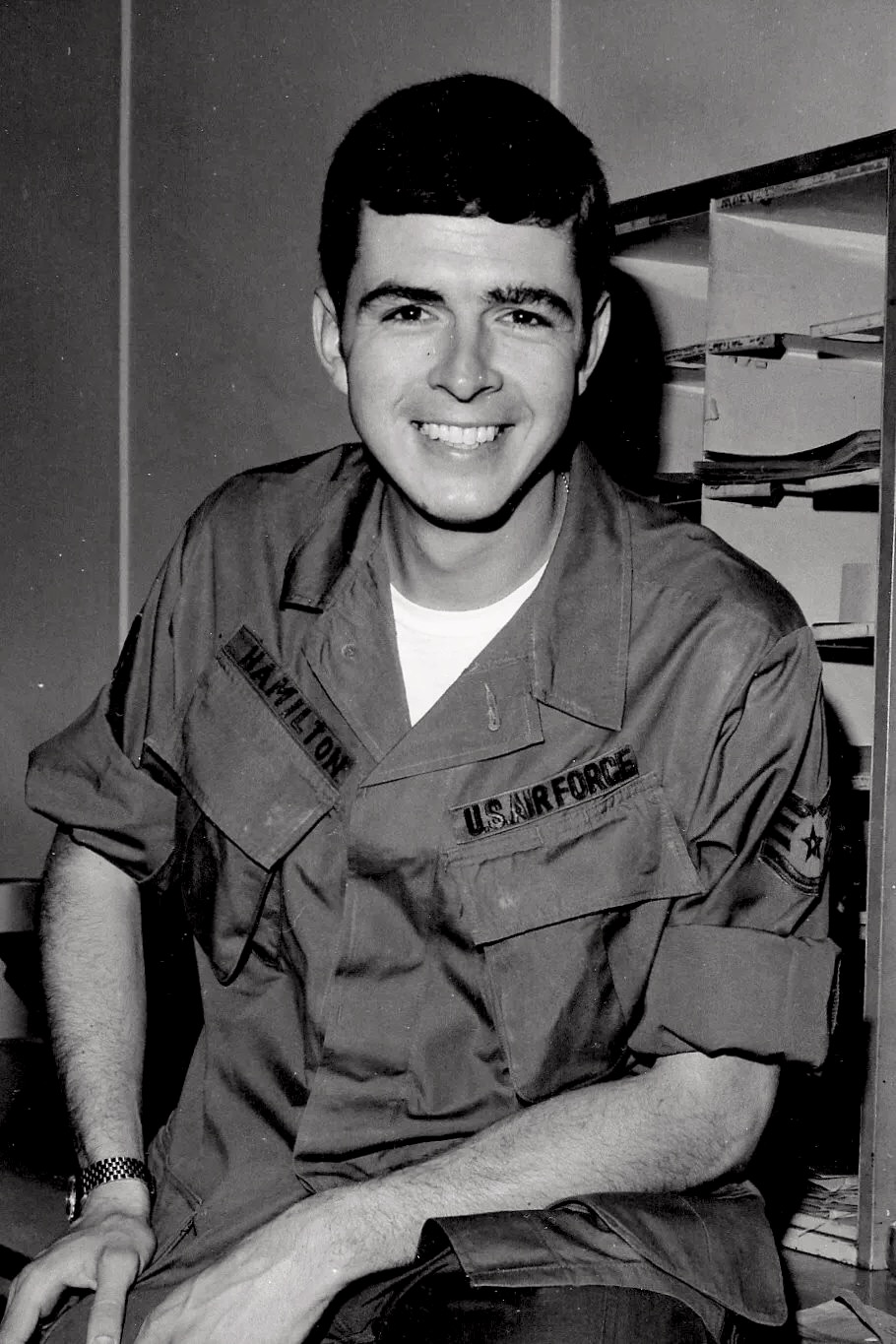

“I still was wearing my Army stuff when I came back in 1972,” says Jim Hamilton. “I couldn’t get in that jacket now.”

Like DeLamater, Hamilton had enlisted in the Air Force and attended basic training in Amarillo. He arrived in Saigon in 1969, six months after DeLamater, and was placed in the same unit at Tan Son Nhut Air Base. When word got around that there was a new guy from North Carolina, DeLamater quickly introduced himself. The two built a friendship on their shared love of North Carolina college sports and discovered that they would both be returning to Campbell after the war.

After one month in the mail room, Hamilton expressed an interest in working at detachment headquarters. He was transferred there and began typing up handwritten messages to be encrypted at a speed of about 150 words per minute.

Hamilton left Vietnam on Aug. 22, 1970 (two days before DeLamater), and returned to North Carolina. He used his cash from the war to pay his tuition at Campbell, where he had registered in the nick of time, right before closing on a Friday evening before shipping out for Vietnam on the following Monday. Hamilton had attended Eastern Carolina University for a year before serving, but transferred to Campbell because of its size and proximity to his home in Raleigh. He graduated from Campbell in December of 1972 with a BA in Business Administration.

___________________

It was at Campbell that Hamilton and DeLamater reunited and met Charles Malone, an Army veteran of the war. Prior to the draft, Malone had been working as a police officer on Capitol Hill, so he was selected as Military Police by the Army and attended basic training at Ft. Polk in Louisiana. He was one of eight soldiers selected from more than 150 men to be trained for riverboat patrol — one of the most dangerous jobs in Vietnam.

One night during his training, Malone was delayed on his way to a field exercise, and unable to pick up his sleeping bag. He asked another trainee to grab it for him — but when he arrived at the site, his friend had forgotten. That night he slept on a freezing cot in an uninsulated metal hut on the riverbanks. He learned the hard way that teamwork would be critical. It was a turning point in his thinking about his time abroad.

“My anti-war thinking — so deeply implanted in my brain during my college years — was too ephemeral to hold up as a counterbalance to my obligation, as I increasingly saw it, to do right by my riverboat colleagues in arms,” Malone wrote in his memoir.

Malone completed his training and arrived in Vietnam in Spring of 1971, only to be informed that riverboat duty had been given to the Vietnamese. He was given the option to patrol the streets of Saigon instead, and took it, spending his shifts on patrol with two Vietnamese men.

Unlike many popular depictions of war in Vietnam, he was not fighting in the jungle. All of the action he saw — no small amount — was in the urban setting. There were frequent assaults, knife attacks and shootings. He crawled his way out of a cafe after a bombing that killed 17 people and watched the child who had thrown the grenade ride away on a scooter.

“We learned never to touch Zippo lighters — they were often booby-trapped with explosives that would blow your hand up,” Hamilton recalls. “[The Vietnamese] would plant children on the side of the road with explosives rigged to the bassinets, and nurturing G.I.s trying to help would be killed, along with the child. There were drive-by shootings. It was true street fighting.”

“It was turbulent, it was sensitive, it was hot and crowded, and you didn’t know who would come after you,” Malone says. “Our presence created inflation, and those who couldn’t profit off of us with bars and taxi cab services were resentful. Often smiling faces that hid the fact that the vast majority were sympathetic to their own people. I felt that we were intruders in their eyes. You got this sense by 1971 that there was no end plan, and that made it difficult to maintain morale.”

Malone spent a total of 21 months in the Army. He left Vietnam in 1972 and returned to Campbell, where he remembers that his service was mostly met with indifference from his fellow students. He graduated in 1973 with a degree in political science.

Malone was one of many soldiers who strove not to let his opinions on the war interfere with his duty.

“A lot of us were just over there trying to do our best despite our doubts,” Malone said. “We could not let our protest become a liability.” A line from Lord Alfred Tennyson’s 1854 poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade” often went through his mind: “Ours not to reason why, ours but to do and die.”

___________________

Malone, Hamilton and DeLamater can list names of friends from all over the country who died from after-effects of Agent Orange, a popular foliage killer used to cut through the jungle that is heavily toxic. They remember friends from high school and college who signed up for the reserves hoping to stay in the United States, only to be deployed and wounded in battle.

They recall hearing Walter Cronkite on the nightly news after their return, reporting on military actions in ways they found misleading, if not outright untrue. They each had their doubts about the decisions made in Vietnam. But all three said that, given the chance, they would serve their country all over again.

In the past 25 years, DeLamater, Hamilton and Malone say they have been met with more gratitude for their service than ever before. When they first returned from the war, they were advised to wear civilian clothes instead of uniforms to avoid being spat upon or harassed. But perhaps thanks to its strong ROTC program and proximity to Fort Liberty, Campbell campus was welcoming to those who had served even in the 1970s.

“Everyone complained about the food at Marshbanks, but after Vietnam it tasted great,” Hamilton remembers. “Campbell was a welcoming place if you fit the mold … It was a tense time of strong opinions and real concerns, but you could laugh with each other, have dialogue together, go back and forth and just disagree. I’m not sure if that’s the case anymore.”

After Campbell, DeLamater got a business degree and worked in paper and insurance. Malone managed a small home improvement company and was editor for Harnett County News on the side before transitioning to human resources for the secretary of the state — always writing. Hamilton worked for Ross Laboratories and introduced Ensure nutrition drinks to North Carolina before turning back to his Air Force roots in aircraft sales for forty years.